Global Village was the classic Silicon Valley success story. The right people were at the right place at exactly the right moment with just the right product for it to take off a become a big success.

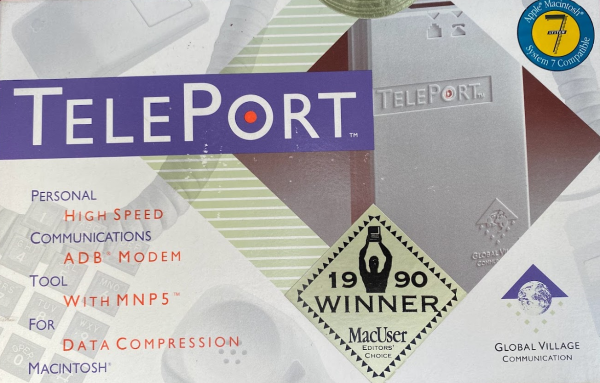

Global Village was founded in 1989 and launched straight into the Macintosh modem market with a unique design and the best fax software to be found.

But the company did not really find success until it happened to be first out the gate with a high speed modem for the brand new Apple PowerBook computers in 1991, a market which it came to dominate.

But even as that was happening it was pretty obvious that this particular success couldn’t last forever and that the company needed to build on its new found fame and fortune by expanding beyond that one focus. The first thing to do was to grow and exploit the Mac modem market. After a high speed PowerBook modem, that meant a high speed modem for Macintosh desktops.

But that really isn’t a new product line, even if the hardware is different. The founders of the company, and especially the VCs that invested in it, wanted to go public, wanted the company shares to be listed on the stock market for sale.

Not so many years down the road during the dotcom boom many companies would go public without making any money, much less having more than one product line. But GV was at the tail end of the era of responsibility, and Wall Street was insisting that we needed TWO successful product lines in order to go public… and all modems lumped together counted as just one.

They say fewer than one in ten Silicon Valley startups find any sort of success. I would say that of the ones that do find that success, the ratio of those that can find a second success are even less likely to occur. Second acts are rare in Silicon Valley, as they are in life, and all the more so second acts that equal or exceed the initial success.

Google, as an example, despite all of its products, still pretty much makes all of its money on ads. They actually try to break that out some, to look like they aren’t completely funded by a single source, but injecting ads into search results and injecting them into YouTube videos seems to be splitting hairs at best. Google is a on product company with a bunch of science experiments to keep the founders busy.

Apple is a rare exception, with the iPhone eclipsing the computer business. Most companies struggle to find that second success. And back in the ealy 90s GV needed that second success to go public.

So we ended up with OneWorld, the network fax, modem, and remote access server. It was a network device that used PowerPort modems… they were small and modular and using that form factor meant we could introduce upgrades in connection speed by swapping in a new modem… to drive a small company focused communications hub business. Everybody in your office didn’t need a phone line for their modem, they could just use the pair in the OneWorld box as a shared resource. They could dial out or send faxes… or even receive faxes, though that was the tricky bit. And it could also be setup to act as an AppleTalk Remote Access server, which was the new hotness in the Apple world at the moment, and something that GV helped develop (we were contracted to help with development) so we knew how to build that in.

That was enough to get us over the second product line requirement. We pushed a bunch of them into the distribution chain, enough to make it look like a success, got Wall Street’s blessing, and went public so people could cash out.

My first IPO. There is a whole story around that and I am saving that post for the anniversary of the event, but for now it is sufficient to say “Op success!” and move on.

OneWorld was a modest success at best. The name itself was a problem. Internally we had called it “NetFax” for years, but research showed that quite a few other companies had claims and trade mark filings on that name. About twenty ideas down the list somebody hit on OneWorld, somehow connecting it back to the ideas of Marshall McLuhan, which is where the Global Village Communication name came from.

The name was mocked in engineering, where it was quickly substituted in to the lyrics of the intro song to the Wayne’s World skit on Saturday Night Live, “OneWorld! Its party time excellent!” But we couldn’t come up with anything better and, even if we had, that decision was made elsewhere.

OneWorld sold enough units to justify its existence, but at the time we were making peak revenue from the PowerBook 500 modems, having given Apple a bill of materials cost for each unit then, once the pricing was settled, immediately finding ways to reduce the build cost. It was fat city while PowerBook 500 modems were selling as fast as we could produce them.

That ended up being a problem. Once you’ve gone public your best performing product line becomes the benchmark for everything else you do, and anything new that doesn’t at least match that mark is automatically a disappointment or failure. This is tricky for public companies, and I have a bit of sympathy for Blizzard hiding their WoW numbers because most quarters in the last 20 years there were carried by WoW.

Global Village needed another success. If you’re not growing, they you’re dying.

One of the first things we did, flush with money from the IPO, was make international versions of our modem lines. There had long been a gray market for GV modems overseas. Given there were few options when it came to PowerBooks, PowerPort modem boxes were all over Japan and Europe. We even low key supported specific issues. I remember there being a problem connecting to Minitel with one of our units so I spent some time working with a guy in Paris and making long distance calls to connect to the French online service to get that resolved. (Foreshadowing of eWorld, it was a connection script issue.)

Now, as a real public company it was time to get our modems certified overseas so they could in the normal distribution channels. This was a pain in the ass because this pre-dated standardized EU certification so we had to get a pass for several countries, each of which had their specific demands. I remember we had to put a plastic shield over the phone jack for UK units because there was a special shielding requirement, while the French had their own variations on line surge protections, and the Germans were insistent on some of their own pet parameters.

But we got it done and there was indeed a boost in sales overseas. Sales grew and our stock price went up.

The modem market, or at least our little protected Macintosh slice of the market both home and abroad, was still buying our products, often upgrading to new GV modems as connection speeds increased. We went from 2,400bps to 9,600bps to 14.4Kbps to 19.2Kbps to 28.8Kbps over a few years, and 33.6Kbps was coming. But the public phone network would eventually put a cap on that speed.

Analog phone lines have an absolute cap of 64Kbps, but in the US, due to robbed-bit signalling… a bit is used every frame to keep the connection in sync… 56Kbps is the theoretical maximum throughput. You could achieve it in ideal conditions… in the lab on a simulator or if, like me, you made sure your ISP was on the same switch in the central office as your own phone line… but it was more aspirational than a dependable connection speed. When we got there modems would return the 56,000 connect message, but it was a lie most of the time.

So the modem market was going to be ending for speed upgrades. At some point 56IKbps would be the norm and easy sales on that front would dry up.

The fat times with the Apple PowerBook modems was coming to an end as well. The PowerBook 500 series was the peak for that. The follow on PC Card modems were a standard format so the only advantage Global Village had was its fax software… and while faxing wasn’t dead yet, email was becoming the norm and connecting to the internet was the quickly eclipsing any interest in faxing.

Meanwhile the Macintosh market share, which had been climbing during the PowerBook era, was starting to shrink. Competitors had learned from Apple and Microsoft finally had something akin to the MacOS ease of use in Windows 95, so even if GV was dominating that market, it was a shrinking domain. Win95 meant companies like Compaq could offer bundles like the Performa line with bundled software and faster hardware at a lower price. Tough times were in store for those who made the money in the shallow pond of the Mac market. Things had changed a lot between 1991 and 1996.

And the Windows modem market, while huge, was extremely cut-throat and GV had nothing really to offer there. A couple of tentative forays into the Windows arena ended quickly.

And even the OneWorld network server was having issues. Designed when 14.4Kbps was the hot new speed for modems, it was found that it wasn’t really up to the task of running a pair of PowerPort Platinum modems at 28.8Kbps simultaneously.

Global Village needed an out. Its core business was decaying and the mothership in Cupertino was looking ill. So the company set out to do what a lot of public companies do… buy other companies and hope that would lead to success.

Telephony tales so far:

- Hanging on the Telephone

- Calling the Mall

- Finding Friends with the Popcorn Lady

- Jenny and the FCC

- What Your Area Code Used to Say About Your Location

- I Get a Modem then Start a BBS

- Tech Support at the Village

- Dominating the PowerBook Modem Market

- The Death of eWorld

- The Great Dial Tone Drought of 96